Could letters serve as a gateway to the mind? To a person's innermost thoughts and feelings? Is it possible to peer into the psyche of a person by reading their letters? Maybe, maybe not. In retrospect, we cannot know how much a person pours of themselves into their correspondence. Are they truthful or reserved? Do they have an agenda? Did the writer consider their legacy when composing letters that would potentially shape the way they are remembered? All of these questions come into play when historians explore primary sources such as correspondence.

At Staatsburgh, we often lament the lack of letters and personal papers left behind by the Mills family. While the family donated estate lands, outbuildings, the mansion and its furnishings to New York State, any personal papers were removed by the family. Letters from Ruth and Ogden Mills do exist in the archival collections of the recipients and there is always more to find. Even though correspondence to or from Ruth and Ogden Mills is thin, a treasure trove of letters from Ruth's grandmother, Margaret Lewis Livingston (1780-1860) exists and were recently annotated and published by Mary Mistler. This essay will share some of the insights about Margaret's life that can be gleaned from reading through all of these letters.

|

| The annotated book of letters from Mary Mistler and Staatsburgh's typewritten transcripts of the letters. Mistler's book is currently available for purchase in Staatsburgh's gift shop! |

This portrait of Margaret graces Staatsburgh's main hall and provides a daily visual connection to her existence. It is easy to look at this painting every day and view her in a two-dimensional way like a portrait. Looking at the painting, we see Margaret as just a series of facts. We know she was the grandmother of Ruth Mills, lived here at Staatsburgh, and died over 160 years ago. It is tempting to judge Margaret from the dour look on her face, and many visitors do, but her letters provide the opportunity to get to know an actual human being with thoughts, worries, and many, many opinions. She may have lived in a different era, but the important components of her life as wife, mother, and daughter reveal feelings that are universal and timeless. The letters provide a front row seat to her life as the only child of a powerful and wealthy man, a mother of twelve, a doting grandmother, and a woman who just plain made things happen.

|

| Margaret Lewis Livingston (1783-1860) Date and Artist Unknown Staatsburgh SHS, NYS OPRHP |

.jpg) |

| Gertrude Livingston Lowndes (1805-1883) Miniature watercolor, attributed to Henry Inman, ca. 1825 The Gibbes Museum of Art |

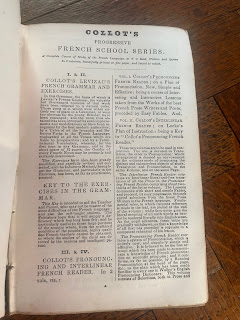

One of the ways that Margaret was continually involved in her children's lives revolved around their education. Margaret managed the tutors and subjects that were part of her children's education. In stark contrast to the way young men were shipped off to boarding school by wealthy families during the Gilded Age, it was not as common for boys to be sent away to school. Girls were traditionally tutored at home, but many of the tutors that Margaret hired were also teaching her sons and grandsons. Margaret was also in charge of her daughter Mary's children for a time while Mary recovered from illness in Europe and we have a few of the books they used in their studies. It seems that Margaret's grandson William Lowndes enjoyed writing in his school books!

|

| Inside this French textbook, young William Lowndes wrote a poem about his older sister Margaret "Maggy". It reads, "Maggy is little maggy is small gaggy likes to go to a ball." Perhaps "gaggy" was a nickname for his sister; a nickname that only a little brother could get away with! |

Margaret's youngest daughters, Angelica and Geraldine, were both at home during the course of these letters and she referred to their education the most. Some of the subjects that they studied include English, French, German, mathematics, music...and dancing. Margaret wanted her daughters to be both well educated and marriageable. Margaret's young sons who remained at home also received instruction from tutors on subjects such as French, German and English. In a letter dated January 18, 1838, Margaret wrote, "We have not yet succeeded in procuring employment for Lewis. He is taking French lessons with Henry and Geraldine. Angelica has a German teacher and the last three have an English teacher." Although Lewis was already 24 years old at this time, Margaret still finds it her role to help him find a job and become more employable by bettering his languages. Margaret also continued to empower her daughters and provide them with an education that ensured their scope of knowledge went far beyond that of running a household.

.jpg) |

| Angelica Livingston Hamilton (1820-1896) Artist: George A. Baker (1821-1880) Staatsburgh SHS, NYS OPRHP |

Early on in their correspondence, just two months after Gertrude had married, Margaret continued to comment on Gertrude's writing, providing encouragement and even a bit of constructive criticism to her 21-year-old daughter. A letter from December 31, 1826 reads, "You write with spirit, with originality; your sentences are not only perfectly correct, they are frequently elegant and the few inaccuracies that sometimes occur require only a little perseverance and attention to remove." Always a teacher! Always a mother!

While Margaret arranged social entertainments for her daughters to mingle in society and find suitable spouses, she also worked with her husband and father to help to secure jobs for her sons. She consistently worried about her son Alfred who suffered from alcoholism. On May 9, 1837 she wrote, "Alfred has not yet arrived. I long, yet dread to see him. What can I do for him? How shall I save him? My prayers, I fear, are all I can give him." During the course of these letters, Alfred went through various jobs, but never held a position for very long. He had many relapses and would spend time at home convalescing and dealing with depression. Alfred was Margaret's only child who never married and was the first to die. He died in 1855 at age 52 while his mother was still alive.

Grandmother, Mother & Matriarch

Margaret's deep love for her children and grandchildren comes through in her letters. While she likely would have never admitted this to her other children, her letters to Gertrude reveal Grandma's special affection for Gertrude's children Dudy (Julia) and Mai (Mary). In a November 28, 1834 letter she wrote, “I fear Grandmamma can never love any of her grandchildren as she does them, unless Aunt Mary should have a dear little girl. None of the others can rival my Dudy and Mai. I love the parents as much as I do you; but the children do not twine round my heart as yours do; even Julia’s boy does not interest me as my darling Dudy did.”

|

| Margaret Lewis Livingston, circa 1798 Mezzotint engraving, Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin National Gallery of Art |

As much as Margaret loved her children, she did not seem to be quite as fond of their spouses. Her strongest criticisms were reserved for her daughters-in-law. It clearly took some time to win over Margaret and prove that you were good enough for her beloved children. The eldest child, Morgan, married Catharine Manning in 1829 and although they didn't always see eye to eye, Margaret remarked that Catharine improved upon acquaintance. Margaret's most scathing review in these letters concerns Louisa Storm, the wife of her seventh child, Robert. In an April 24, 1838 letter, she wrote "Louisa is so very silly, her temper so hard, so utterly selfish, that is makes me sorry for poor Bob every time I see them together. His disposition is so affectionate that he would love anything that appeared to love him, and I doubt she even loves her children. She asserted the other evening that she had never kissed either of them." The accusation that Louisa did not love her children was considered a mortal sin by Margaret. It is unknown whether Louisa ever improved upon acquaintance, or whether the marriage was in a good state, but certainly divorce was not an option.

During the course of these letters, in 1838, her son Lewis became engaged to Margaret Maria Livingston, daughter of Robert L. Livingston of Clermont. She was the granddaughter of the Chancellor Robert R. Livingston who was also Margaret's uncle. She was both a distant cousin and, according to Margaret, an imprudent match. She had no money and Margaret warned that they would have to wait many years to receive inheritances to live on. In a letter dated September 24, 1838, Margaret wrote, "He knows that she has nothing; that his own prospects of getting any thing to do are worse than ever...She has so few attractions that I have little to hope from her inconstancy; she is amiable and affectionate; that is all. She has no beauty, no grace, no fashion. She is not clever and has very little improvement of any kind. I do not want this engagement spoken of, for I still hope it may be broken off." Needless to say, in 1840, Margaret Maria married Schuyler Livingston, another distant cousin. We don't know what happened to end the engagement, but Lewis eventually did marry a woman named Julia Boggs in 1843. For his sake, we hope his mother approved this time.

Staatsburgh

These letters also provide some clues about the Staatsburgh estate Morgan Lewis built in 1832. Although the family was primarily based on Leonard Street in New York City, they traveled to Staatsburgh for the whole summer in addition to other times throughout the year. Just as she was very present in her children's lives, Margaret also seems very hands-on when it comes to the estate. In a letter dated September 24, 1838, Margaret wrote, "Puss [daughter Geraldine], Maggy [Mary's daughter and Margaret's granddaughter] and myself have been down to the new garden to lay out a shrubbery. I wish to remove the greater part of the shrubs from the house to the other garden." I can't say how much of this work Margaret did herself and how much she directed an employee to complete, but it is clear that she was very involved and invested in the estate. Half a century later, Ruth and Ogden Mills were hiring staff to do this type of planning and work.

|

| Staatsburgh, 1832 house, East Portico |

Margaret's letters also include a few other details about her time at Staatsburgh. It was a lot of work to prepare to move to the country for the summer, and she was tasked with overseeing the packing and making sure they had enough servants. She would also hire tutors for her children who would be stationed at Staatsburgh for the summer. Once they were ready to leave the city for the summer, they took a boat to Staatsburgh, which was the most expedient way to travel to the site in the 1830-40s. Margaret would often refer to Staatsburgh as "home" in her letters, and it is clear that she enjoyed her time here. In a May 28, 1838 letter she wrote, "I returned here last evening after spending the week at Staatsburgh where everything is fresh, blooming, and beautiful. Oh, how I longed for you all to enjoy it with me. It appeared a sin to come away. It was enough to make even me romantic to see the blossoms wasting their sweetness and the birds their music with no one to admire them."

|

| Staatsburgh, 1832 house, West Side |

Margaret did finally get her wish to have Gitty's family living closer before she passed away in 1860. In 1858 the Lowndes family was recorded as living in New York City and in 1859 Rawlins purchased 65 acres in Staatsburg, less than a mile from Margaret's land. They built a house there which they named "Hopeland." Today the Hopeland property is now state park land even though the home did not survive. In addition, Margaret's youngest daughter Geraldine married Lydig Hoyt (1821-1868) and in 1855 they also built a house in Staatsburg. The Calvert Vaux-designed home, "The Point," was located on the river just to the south of Margaret's own home. When Margaret died, her son Maturin inherited Staatsburg and occupied the house with his family including his wife, Ruth Baylies Livingston, and twin daughters (Ruth & Elizabeth) born in 1855. While the proximity of these households is evidence that Margaret's children stayed close, her letters show her love and ongoing machinations to keep them close. Margaret's eldest daughter, Julia Livingston Delafield, later wrote a book about her well-known grandfather and great-grandfather, Morgan and Francis Lewis. In that 1877 book entitled Biographies of Francis Lewis and Morgan Lewis, Volume II, Julia's quote about her mother seems to truly encapsulate Margaret. Delafield wrote, "Every detail of the management of the estate, as well as of the household, passed through her hands--not from any love of control on her part, or because the heads of the family were unwilling to take their share of the burden, but because she was the center round which everything revolved."

******************

For a further look into the lives of Gertrude Livingston Lowndes and her sister Mary Livingston Lowndes, take a look at this 2016 Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook article by Melodye Moore entitled "A Tale of Two Sisters." The article examines the two women and their Southern plantation owner husbands amidst the struggles of the Civil War Era.

Fascinating look at a strong and capable woman. So often women's lives and accomplishments are lost in history.

ReplyDelete